Why can't I draw the images that are in my mind?

It's easy to conjure a mental image, but somewhere along the line, the image gets distorted. Of course drawing is both a skill and a talent, and producing great art requires tons of practice. But why is it that unskilled artists struggle so much with getting an image down on paper? What happens between the brain and the hand?

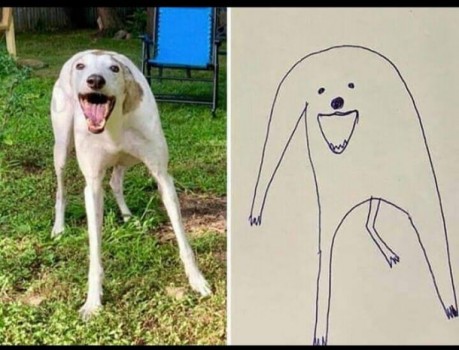

A famous example:

Answers ( 1 )

There are two different skill sets at work here: drawing accurately from observation, and the ability to visualize or memorize.

Problem Number One: Accurately Rendering Reality

In college (sometimes high school) drawing classes instructors will often require students to make a series of blind contour line drawings, observing and drawing a group of objects while never looking at their paper. They start out laughably terrible, then gradually begin to resemble the still life that is being observed. This is done to break the bad habit that many people have of looking at their subject, then staring at their paper or canvas and drawing their memory of the subject. You are allowed to start glancing at the drawing a few times, then more often, eventually deciding when to look at each but being reminded to spend as much time as possible looking at the subject while drawing. You are learning how to observe closely in detail while training your hand, eyes and brain to work together.

Another part of learning to draw is to becoming adept at analyzing shapes (2D) as well as forms (3D) in order to reproduce them accurately. Many (not all) people learn to do this by practicing drawing basic solid forms well such as cubes, spheroids, cylinders, cones, pyramids and prisms, by studying light and shadow, and by learning various principles of perspective. Part of rendering a complex form well is observing and understanding how forms look from different angles, how they distort under pressure, but especially how they cover parts of other forms they are near or that they touch. As with any skill, people who have talent will acquire it faster and with more ease than others.

Many people simply have not invested the time and effort required to achieve the level of representation that they desire. The example you’ve provided does resemble the reference photo enough to be recognizable, just not as much as many people would like. If a very young child produced that drawing, they would hailed as a prodigy while their peers are all drawing smiling blobs that have four lines protruding to symbolize arms and legs to represent every person or animal that they draw. As adults we tend to expect better performances from ourselves than when we were young and unsophisticated at everything, but should we laugh at people who can’t calculate linear regressions? This type of math is introduced in Algebra 2 classes, which are within the reach of high school students. Many people never learned how to do them, never learned it well, or allowed the skill and knowledge to atrophy over time. Does everyone remember the difference between stratus clouds versus cumulonimbus ones?

Problem Number Two: Visualization vs. Imagination

The degree to which people can visualize varies from aphantasia (complete inability to visualize) to eidetic memory (extraordinary high precision memory of something seen once.) Most people fall somewhere in between these extremes. Research in neurology in recent decades has revealed how fragmentary and inaccurate that both our senses and memories are. Our brains employ all sorts of hacks to create the illusion of seamless, high quality sensory information, and memories of events are more of a story that our brain tells itself and little like a literal recording.

We frequently feel as if we have a clear image of something in mind but it is usually more of an overall impression of that thing with fragmented, fuzzy details. Our minds are such amazing pattern matching machines that we often don’t need a terribly accurate impression of something to categorize things. From your mental image you have, can tell me what color the fur on your dog is or the color of the horn on your giraffe-unicorn is, but can you tell me how large the muscle mass is where the shoulder of the front leg connects to the torso, the ratio of the diameter of the ribcage to the haunch, the length of the snout compared to the height of the head? How precisely clear is that image that you think is vivid?

Faces are famously hard for most people to learn to draw because our brains are so eager to find face patterns. Anything vaguely resembling a face is happily accepted as “close enough” by the unconscious mind, leading us to see faces in automotive grills, buildings, dark spots on toast, and three prong electric wall sockets. Entire websites are dedicated to this form of pareidolia. Much of art training is learning to ignore much of the mental shortcuts that helped to keep hunter-gatherers alive for several million years.

An example from WTF@CE

Our imagination complicates things, since it rushes in to provide details which we misremember, did not observe well, or have not seen at all. Compare Dürer’s masterful Praying Hands drawing rendered from observation to his amusingly incorrect woodcut of a rhinoceros done entirely from descriptions and his imagination. In designing monsters and aliens as a special effects makeup artist, I can draw and sculpt very original things by simply rendering random forms, but if I want it to feel real to observers I need to combine masses, details, features and textures from real creatures combined in unusual and surprising ways. When I age a performer or create a resemblance, I have to work in a hyper-realist mode to be able to create an illusion that audiences will believe. I use a lot of references!

Albrecht Dürer’s Praying Hands from Wikipedia

Dürer’s attempt at a rhino that was described to him, from Wikipedia

Let’s assume you meet someone who draws horses well without references. They’ve made either a formal or informal study of horse anatomy, regardless of whether they are an animal illustrator or someone who raises or trains horses. If it is accurate, they know how to observe and recreate imagery and have memorized numerous details of that thing or are one the unusual folks with an eidetic memory. It is only because of his familiarity with animals such as horses and elephants that Dürer’s illustration is recognizable as a rhino.

To achieve accurate representation, you need to have good observational skills of the real thing, an image of that thing, or a clear and detailed memory of that thing coupled with accurate rendering skills.

“Realism” Isn’t Everything

While drawing representationally (what people like to call realistic) tends to be highly valued by some people or for specific purposes, artists have always distorted reality to varying degrees. Even Michelangelo, a master of idealized human anatomy, proportion, and detailed representation began to exaggerate torsos and gave rise to the Mannerism movement. Once the camera was invented in the mid 1800’s, visual artists were more free than ever before to use representation less or abandon it entirely.